There are precious few figures in pop music history who can truly be called Icons: singular performers who are without peer. Artists like David Bowie, The Beatles, or Miles Davis, whose legacies overshadow all contemporaries and transcend generations.

There are precious few figures in pop music history who can truly be called Icons: singular performers who are without peer. Artists like David Bowie, The Beatles, or Miles Davis, whose legacies overshadow all contemporaries and transcend generations.

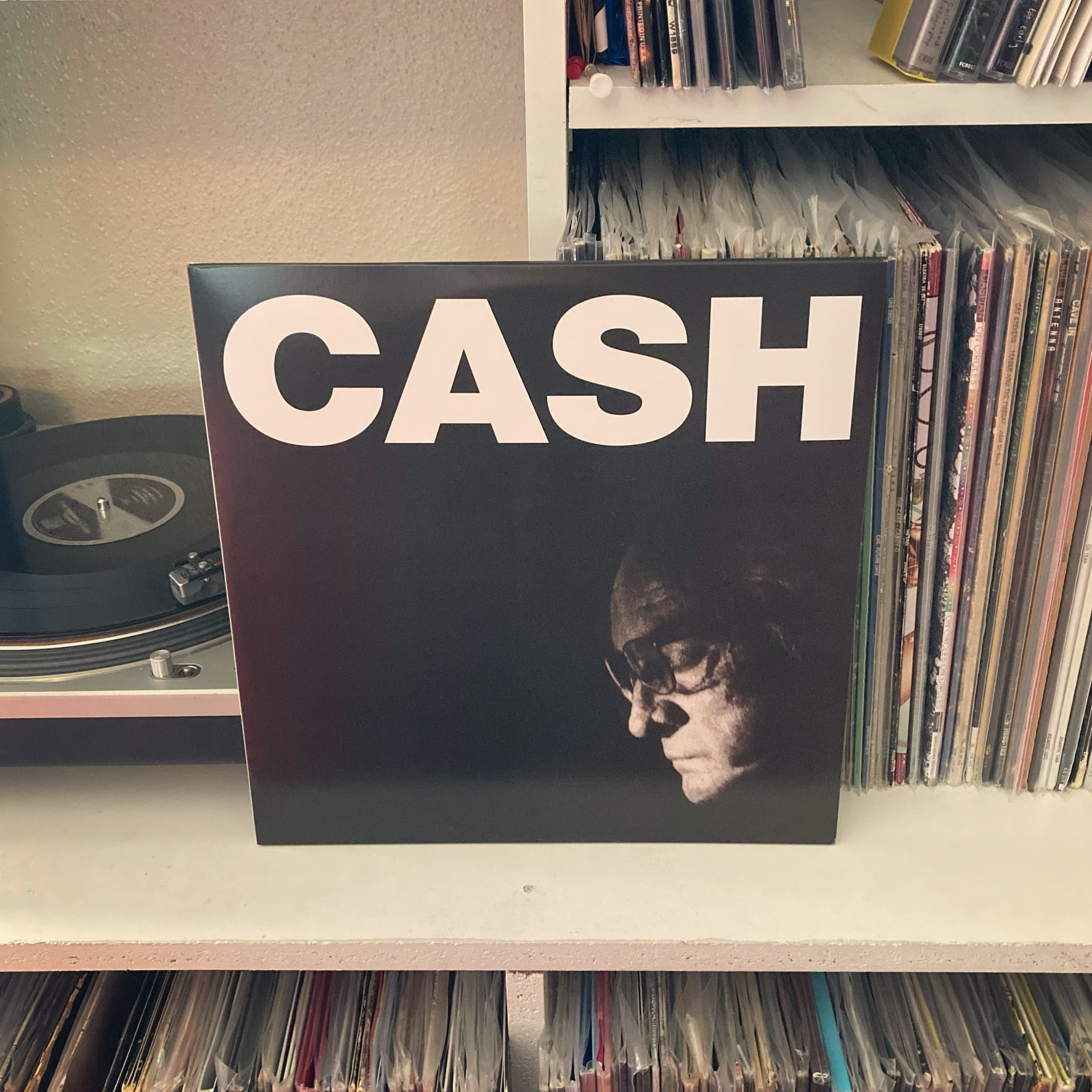

There is no mistaking that Johnny Cash is one of these artists. But one of the biggest reasons his legacy survived as well as it did was his late-career partnership with producer Rick Rubin, who cut his teeth working with hip hop and metal acts like the Beastie Boys, Public Enemy, and Slayer. On paper, the two seem like the strangest bedfellows you could put together. But throughout the American Recordings series, Rubin demonstrated a keen instinct for bringing Cash’s ragged performances to life.

While all of the albums released in the series are littered with gems, none are quite as packed as The Man Comes Around, the final album Cash would release before his death.

Throughout his five-decade career, Johnny Cash offered up countless albums mixing profound original country-western songs with reinterpretations of modern pop classics. American IV offers some of the best of both category, reimagining a few of his previously recorded tunes like “Tear Stained Letter” and “Give My Love to Rose,” the latter of which is given far more gravity by Cash’s own audible mortality (the recording sessions had to pause a number of times due to his failing health).

The title track, however, is possibly the strongest original he ever wrote. Int he liner notes, he speaks of laboring over the song for months—the most time he had ever given a single song. The result is a ragged, fiery song that captures the Man In Black as he truly was: a Prophet of the Lord pointing to the injustice of the world and looking forward to the coming of the Righteous Judge. And with the veil worn thin by the ravages of his illness, he sees more clearly than ever.

Of course, the main event here is the surprising Nine Inch Nails cover “Hurt,” which has a firm spot somewhere in my personal top ten best recordings of all time. Admittedly “Johnny Cash Does Trent Rezoner” sounds gimmicky outside of context—a position that Reznor himself held. But the result is one of the best four minutes ever put to tape. Rubin’s masterful arrangement puts plenty of room around Cash’spalpable regret, elevating a song that could sound like the whine of a twenty-something who just discovered life isn’t always peachy into a torrid lament from a hard-lived life.

But “Hurt” isn’t the only song that undergoes such a stunning metamorphosis. He turns the irony of Depeche Mode’s “Personal Jesus” into a sincere invitation. Ewan MacColl’s “First Time I E’er Saw Your Face” and The Beatles’ “In My Life” take on a rich new meaning when directed to his wife of thirty-five years (she would pass away six months after this album’s release). His treatment of Sting’s “I Hung My Head” is particularly affecting, turning a Country Western tragedy trope into a moving deathbed confession.

The duo also set their hands to old classics, such as Simon & Garfunkle’s “Bridge Over Troubled Water” (featuring Fiona Apple), The Eagles’ “Desperado” (featuring Eagles member Don Henley), Hank Williams’ “I’m So Lonely I Could Cry” (featuring Nick Cave), and the traditional Irish tune “Danny Boy,” all of which carry the weight of an elder recognizing that his time has come and making his swan song.

They’re not afraid to have some fun along the way though—”Personal Jesus” is almost cheerful. “Sam Hill” showcases the same sense of humor seen in songs like “A Boy Named Sue.” “Tear Stained Letter” is just as sardonic as it was in 1972.

Even the closing track, the classic show tune “We’ll Meet Again,” has a bittersweet joy to it that is only made more appropriate by Cash’s death the following year. It’s a fitting capstone to the album where The Man in Black finally looks Death in the face and welcomes him as an old friend.

And while two more wonderful albums have been released with tracks recorded after this, The Man Comes Around is the most consistent, and the most fitting punctuation mark at the end of a long and celebrated legacy.