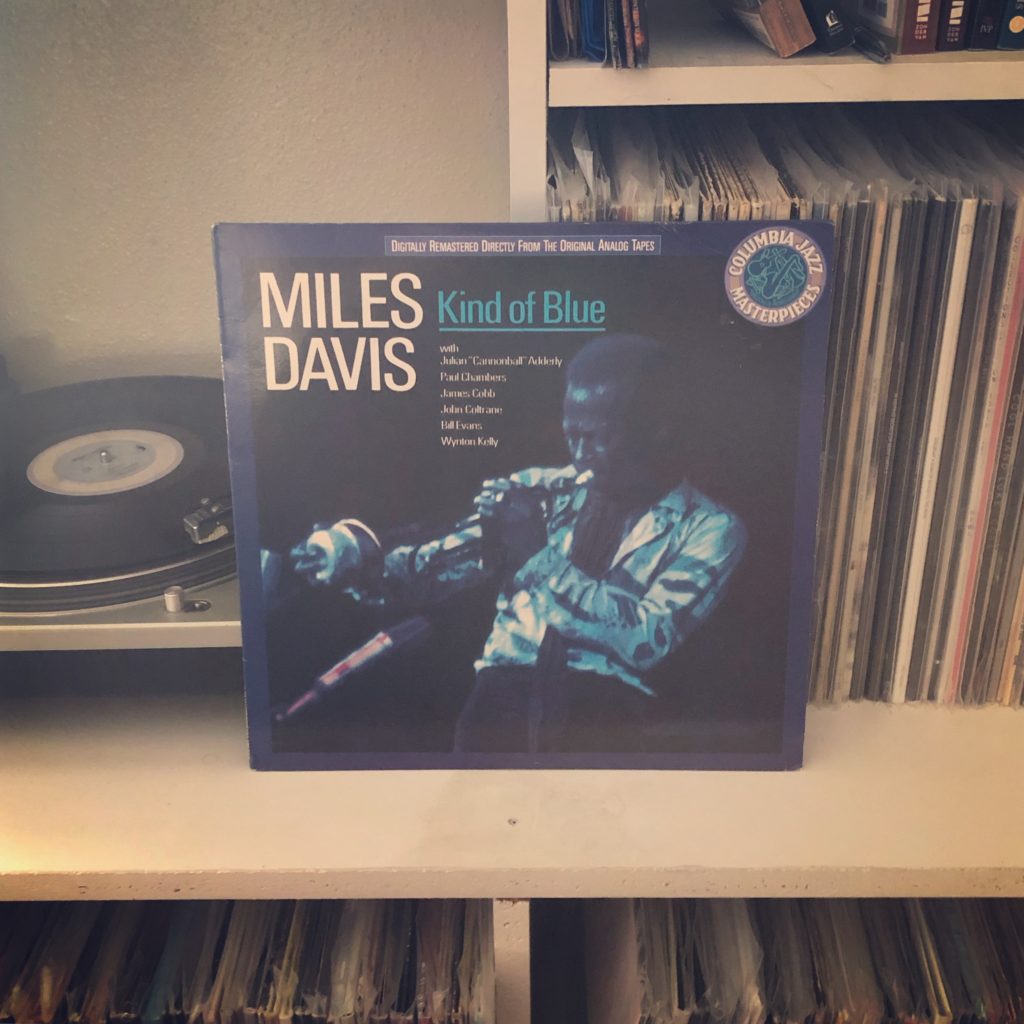

As much as I love Miles Davis’ electric period (especially In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew) it’s taken me until the last couple weeks to realize that everyone else in the room with Miles on those records was also making some really out-there music around the same timeframe…

Maybe the most out-there of Miles’ collaborators during this time was the already-legendary Herbie Hancock. Herbie was a pillar in the jazz scene years before Miles invited him into his band. He had proven himself as a master composer (”Maiden Voyage” is a standard for any high school jazz group) and a virtuoso on the

piano. But when instrument makers started to expand upon the basic format of the piano itself, Herbie was keen to jump on board. He was an early adopter of the Fender Rhodes, the synthesizer, and tape delay.

While you can hear his love for electric pianos on his work with Miles, his fascination with the boundless possibilities of synthesizers came to a head during his Mwandishi period. While all three of these records (

Mwandishi and

Crossings being the other two) saw Herbie and Co. pioneering digital landscapes with sheer animalistic delight, that ethos reached its pinnacle on

Sextant.

The album opens with “Rain Dance,” a nine minute track that is almost as synth driven as a Kraftwerk tune. Drums are almost absent as the group lets a synthesizer take over on rhythm duties. It’s followed by “Hidden Shadows,” which I swear is a rearrangement of a tune from Miles Davis’ Live-Evil, but I can’t identify it. But it jaunts along with a wicked sounding voodoo funk that Herbie tries to defeat with the only acoustic piano on the record (spoiler alert: he does not defeat the voodoo).

Side B is a single twenty track (not unusual during this period) called “Hornets.” It’s a funky, spaced-out jam that sounds exactly like the cover looks. The band plays in an absolutely tribalistic abandon that sounds exactly how the cover looks. Herbie warps the settings on his tape delay. Bennie Maupin plays a friggin’ kazoo. Buster Williams runs his bass groove through every possible permutation. Billy Hart does all he can on the drums to keep the band from flying off into space. But for all of his effort, he fails: the song still ends up as the theme song for a rave on Mars.

While Herbie would go on to out-funk all the funk guys on

Head Hunters, his Mwandishi period produced my undisputed favorite albums in his catalogue. And this record, even more untethered to traditional conventions of jazz, is as good as he gets.

Throughout jazz history, there is perhaps no greater convergence of fiery experimentation and boundless talent than the players that made up Miles Davis’ band during his electric period.

Throughout jazz history, there is perhaps no greater convergence of fiery experimentation and boundless talent than the players that made up Miles Davis’ band during his electric period.

The interesting thing about jazz is that the albums are just as much about the side players as the bandleaders. And if you listen to enough jazz, you start to notice who the major players are.

The interesting thing about jazz is that the albums are just as much about the side players as the bandleaders. And if you listen to enough jazz, you start to notice who the major players are.