In the summer of 2008, three of my best friends from college interned together at their church. Meanwhile, I was interning at a church in a city about 45 minutes away. Throughout the internship, two of them tortured the third, Josh, by singing the hook to “Rehab,” drawing scoffs every time.

The following semester, Josh and I were roommates, and I had drawn much delight from buying records that would annoy or confound him. His look of disgust as he asked, “what is this?” was almost as rewarding as the music itself.

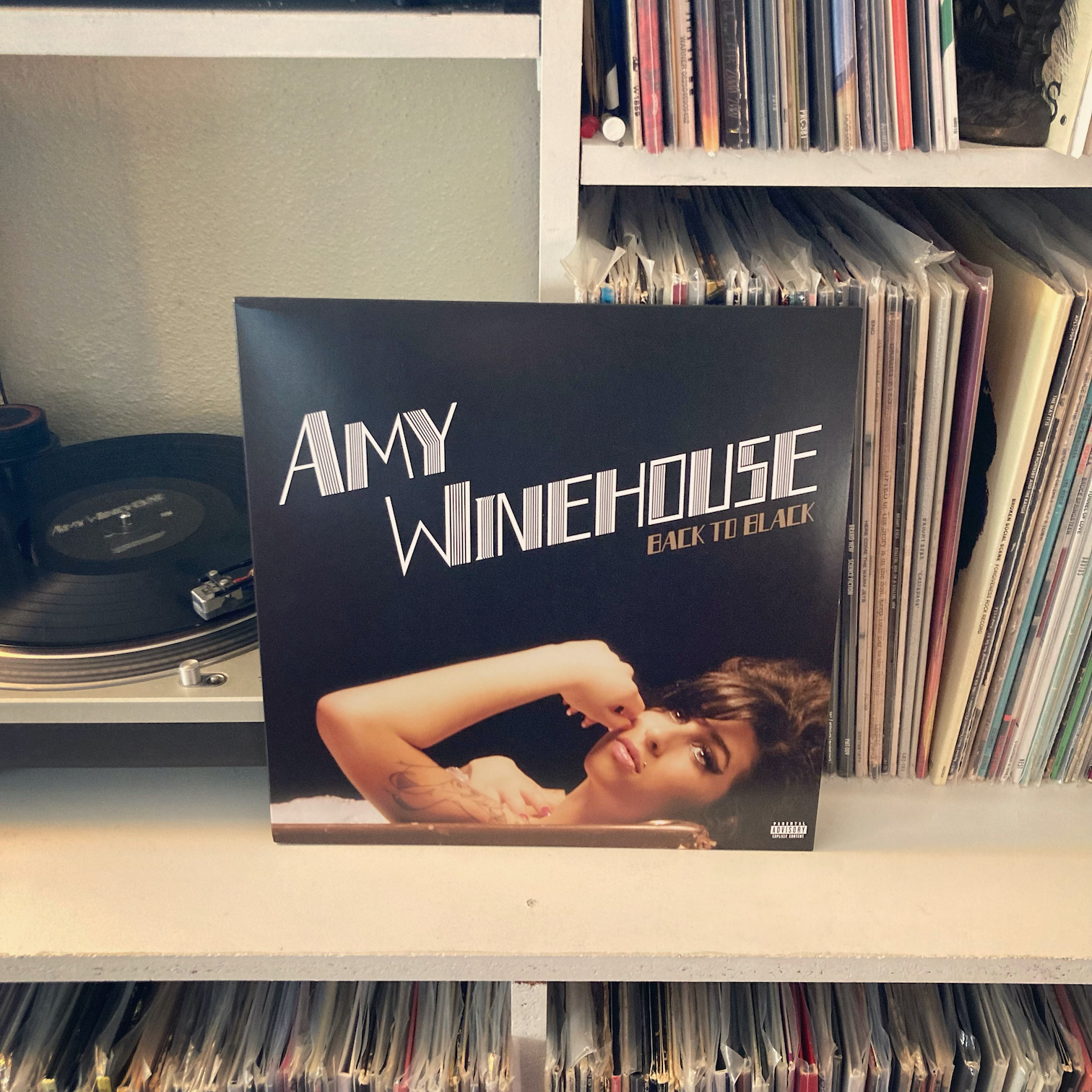

One day, hoping to keep the prank going, I bought a vinyl copy of Winehouse’s Back to Black. To my dismay, he joyfully sang along with every word of the track that tormented him.

I sold the record a few months later, but not before it got its hooks in me. In the years since, I have wrestled with the choice to purchase another copy over and over. This copy in particular was in the “Buy it Later” section of my Amazon cart for months before I accidentally bought it alongside a bottle of conditioner.

Accident or not, I’m glad to have it back.

While this record debuted at number one in the UK, it took a little more time for her to gain the same kind of attention in the States. I was actually shocked to see it came out in 2006, because I didn’t hear “Rehab” until the spring of 2008, and once I did, I heard it everywhere. That renewed attention was the result of the 2008 Grammy Awards, which snagged her five wins.

And while the Grammys often miss the mark entirely, Back to Black is the kind of album you’d hope to win top honors. In a musical landscape filled with cookie-cutter dance-pop, Back to Black was a breath of fresh air. The arrangements were a throwback to the classic soul of the Motown Records era, Winehouse’s impressive voice accompanied by blasts of horns, jazzy guitars, punchy bass lines, ultra-crisp drums, grand piano, and the occasional string section. It won Winehouse and producers Mark Ronson Record of the Year for “Rehab,” but that’s hardly the only noteworthy song on the record.

Every track on this disc is just as slinky and fresh as the lead single, conjuring the image of a Detroit nightclub in the 1960s. The Motown vibe is especially winked at in “Tears Dry On Their Own“—which borrows the instrumental track from Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell’s “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough”—but tracks like “Me and Mr. Jones,” “Some Unholy War,” and “Love Is a Losing Game” are just as convincing. There are also a few hints of reggae and ska, such as “Just Friends” and the dub-like flourishes on “He Can Only Hold Her.”

But the biggest reason this record works so well is because of Winehouse herself. Her songwriting paints a picture of a flawed protagonist who is a victim of her own chaos, but there’s enough sincerity to elicit sympathy or even a sort of admiration. And then there’s her voice—good God, that voice!—rich and smoky, in the ranks of legends like Billy Holiday, Nina Simone, and Ella Fitzgerald. And in hindsight, it’s plain that her success opened the door to other (especially British) soul-tinged singers, such as Ellie Goulding, Florence and the Machine, and even freaking Adele. Spin editor Charles Aaron went as far as calling her the “Nirvana moment” of the soul singer revolution.

Sadly, the demons Winehouse flirts with across the album were all too real, and would end up claiming her life five years later, without the opportunity to record a proper follow-up. Her untimely death gives a harrowing sincerity to these songs in retrospect. However, the grittier details of her life aren’t totally necessary to appreciate this album: it stands on its own merits, and it stands tall.