A couple posts ago, I made a vague parenthetical statement about whether there has ever been an album that has encapsulated the full essence of Melvins. I suggested that The Trilogy—the three-album run of The Maggot’s sludge-doom, The Bootlicker’s avant-pop, and The Crybaby’s covers and collaborations—might have been the closest they’ve ever gotten to offering up a concise CV.

A couple posts ago, I made a vague parenthetical statement about whether there has ever been an album that has encapsulated the full essence of Melvins. I suggested that The Trilogy—the three-album run of The Maggot’s sludge-doom, The Bootlicker’s avant-pop, and The Crybaby’s covers and collaborations—might have been the closest they’ve ever gotten to offering up a concise CV.

But I must confess: I said that knowing full well that it was a lie. Because there is one album that—in my opinion at least—perfectly captures exactly who the band is and what they do.

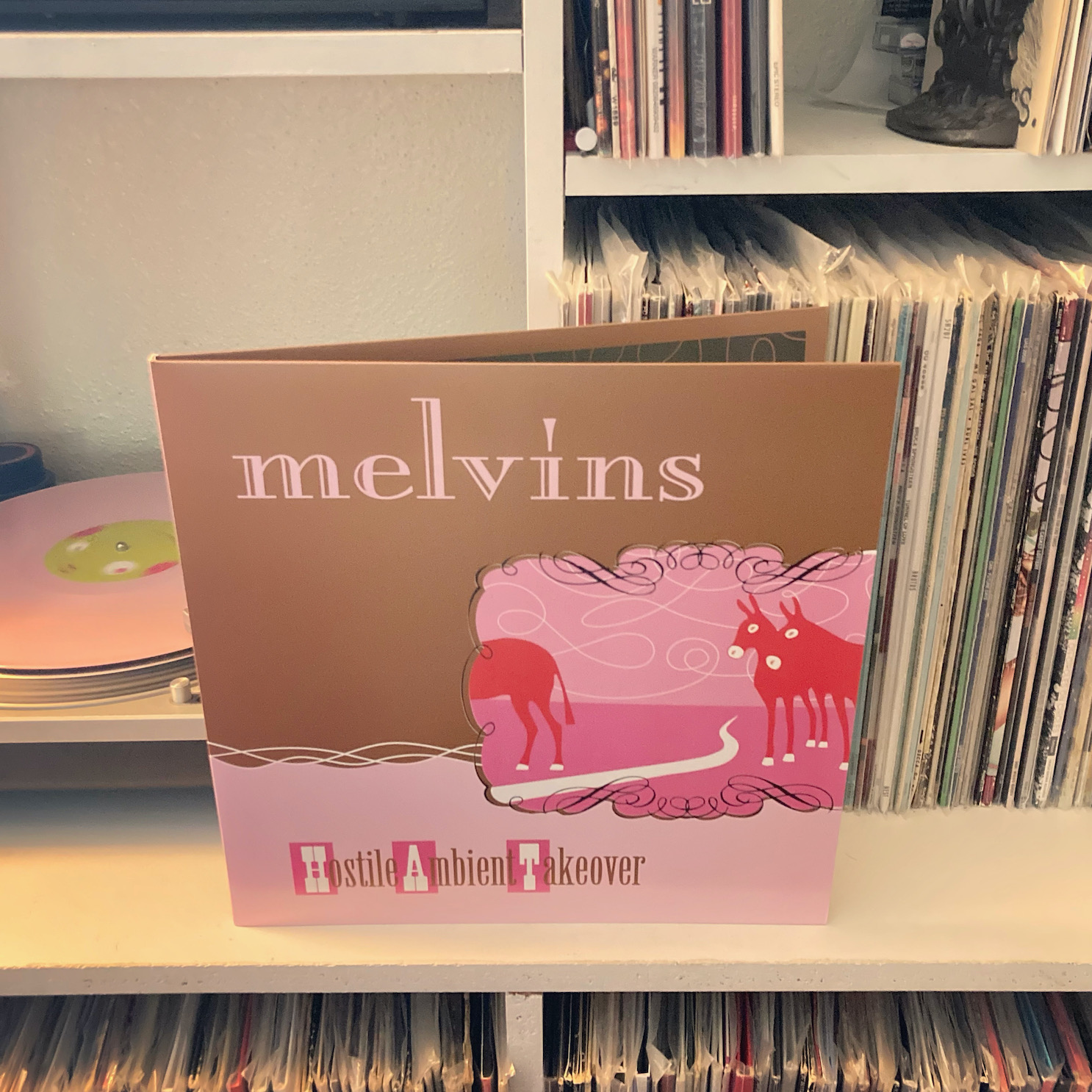

That album is Hostile Ambient Takeover, a title that serves to describe both the eight tracks on this disc and the Melvins as a whole. They are hostile. They are ambient. And they are taking over.

In the booklet accompanying this vinyl reissue, Buzz Osbourne (aka King Buzzo) recounts showing the album to a friend of his, who “just sat staring at the speakers with a hurt look on his face for the full 45 minute duration.” Afterward, his friend said “it’s okay,” and didn’t say another word. That reaction seemed to have been shared by critics and fans alike who panned the album at release. And in retrospect, Buzzo writes, “I knew [they] were wrong. I love this record. It’s one of my favorite Melvins records. I wouldn’t change a goddamn thing about it.” Considering that Osbourne has state many times that he doesn’t remember what songs are on what albums, the fact that this album stands out to him is significant.

That stubborn refusal to compromise on their abrasive weirdness has always been a touchstone of the band’s career—and one that got them dropped from Atlantic Records after three albums. But after a handful of releases on the noise imprint Amphetamine Reptile Records, Mike Patton’s Ipecac Records basically gave them free rein to do what they will.

Depending on whether you count Electroretard as a proper studio album or not, Hostile Ambient Takeover was their fourth or fifth album in three years. And if anyone thought that a few years of indulging their weirdness would have gotten it out of their system, they were dead wrong. HAT instead cranks it up to twelve and flips you the bird if you don’t like it.

The first song, bizarrely split into the two tracks “Black Stooges” and “[Untitled]” on CD and digital (even the vinyl skips track 2 in the numbering), kicks off the record with the most ominous sludge metal they’ve ever made, coming off even heavier than The Maggot. Fuzzed guitar and slide bass churn through a thick off-time riff with Buzzo’s voice growling in the space between. A few minutes into the runtime, guitar and bass both turn to drones, Dale Crover offering up acrobatic drum warfare before the entire song collapses into multiple minutes of feedback. As far as opening tracks are concerned, this is an obvious thesis statement. However, you can always trust Melvins to subvert expectations, and they do immediately after with the blisteringly fast rockabilly of “Dr. Geek,” which showcases the band’s technical chops in a way their sluggish doom metal never could.

The detour is shortlived, as “Little Judas Chongo” is even heavier than “Black Stooges,” with an aggressive energy that approaches hardcore. The tempo pulls back hard for “The Fool, the Meddling Idiot,” a plodding masterpiece that is somehow almost sensual. Detuned guitars and sparse-but-punishing drums grind at a slow, ominous pace, but Osbourne’s vocal delivery is incredibly acrobatic, shifting between a syrupy sweet croon and his trademark rasp, sometimes in the same line. But in the last couple minutes, it practically becomes a different song, dancy drums and synthesizers throwing back to 80s pop. Once that section concludes, Crover’s opening drum solo to “Black Stooges” returns, kicking into the psych-rock “Brain Center at Whipples,” which lands somewhere between Black Sabbath’s druggier songs and Jimi Hendrix’ heaviest moments.

“Foaming” might almost have made it as a radio hit—if it weren’t eight minutes long. Buzzo plays a melodic arpeggio between verses, Rutmanis’ slide bass and Crover’s drums keeping things grounded. But after a few minutes, it’s taken over by an atonal keyboard(?) line and the band is suddenly no longer interested in writing a pop song. Guitar and bass chug through a menacing melody line, Crover changing rhythms on a dime. That line repeats for the rest of the song, slowly being taken over by, let’s call it “hostile” ambient noises.

But all the weirdness of the album up to this point is practically accessible radio rock compared to the sixteen-minute closer “The Anti-Vermin Seed.” A chugging guitar figure is heard, muffled as if it’s being played down the street. Crover offers some plaintive snare lines before he too is muffled through the walls. Droning guitar feedback swells into the foreground as the muted riff continues beneath. Five minutes into the track, Crover’s drum set finally forms a cohesive rhythm, Rutmanis’ bass noncommittally playing along as synthesizer noise fights for control. After three minutes, the synths fade and Buzzo’s guitar finally joins in, thick with modulation. The victory is short-lived, as synths begin to fade in again after a couple more minutes.

Ten minutes in, the drums and bass hush to a near whisper. Finally Osbourne’s voice enters, thick with double-tracking and studio effects, offering vaguely threatening missives with several beats between lines. His lyrics are rarely very concrete, but there’s something apocalyptic going on here that sounds terrifying. “If I could get the nerve and move, I’d put them all to sleep,” and later, “somewhere there’s a king who keeps his days for forgiving everyone.” Between verses, the band punctuates with a thick guitar riff and crashing cymbals, retreating back for verse two. After he’s finished singing, his guitar returns, matching Rutmanis’ bass line with a thick fuzz. Crover stays out for the first couple loops, as if Buzz has to convince him to join in. When he finally does, it’s not quite as punishingly heavy as you might expect, but it’s a classic Melvins riff. And at the end of a track like “The Anti-Vermin Seed”—and an album like Hostile Ambient Takeover—“classic Melvins” feels like a much-needed palate cleanser.

Two decades on, Hostile Ambient Takeover has had a bit of a revisionist revival. While fans reviled it upon release, it’s now remembered as one of their best and most important releases. And it makes sense why. Every element of what makes Melvins Melvins is in top form here. The Buzzo’s guitars are as heavy as ever, Crover’s drumming is top notch, Rutmanis’ slide bass is in full overdrive, Osbourne gives his most varied and impressive vocal performance of any album. Both the metal riffage and the avant-garde weirdness are as fully formed and rewarding as any of their other albums. This might not be the best introduction to Melvins for anyone coming to the band cold, but it’s probably the most emblematic of their entire career. And the fact that they were able to create something this fresh almost twenty years after they started playing together that still sounds fresh almost twenty years later—is a feat in its own.