Like many a white suburban kid, I’ve had a passing fascination with hip hop. I was a pretty big fan of Kanye West until he went off the rails. I know every word of “Rapper’s Delight.” I have a huge appreciation for old school acts like Public Enemy and Naughty By Nature. I’ve even got my own unfinished Jay-Z mashup album.

Like many a white suburban kid, I’ve had a passing fascination with hip hop. I was a pretty big fan of Kanye West until he went off the rails. I know every word of “Rapper’s Delight.” I have a huge appreciation for old school acts like Public Enemy and Naughty By Nature. I’ve even got my own unfinished Jay-Z mashup album.

But when Kendrick Lamar came on the scene, I completely lost track of what was going on in the world of hip hop.

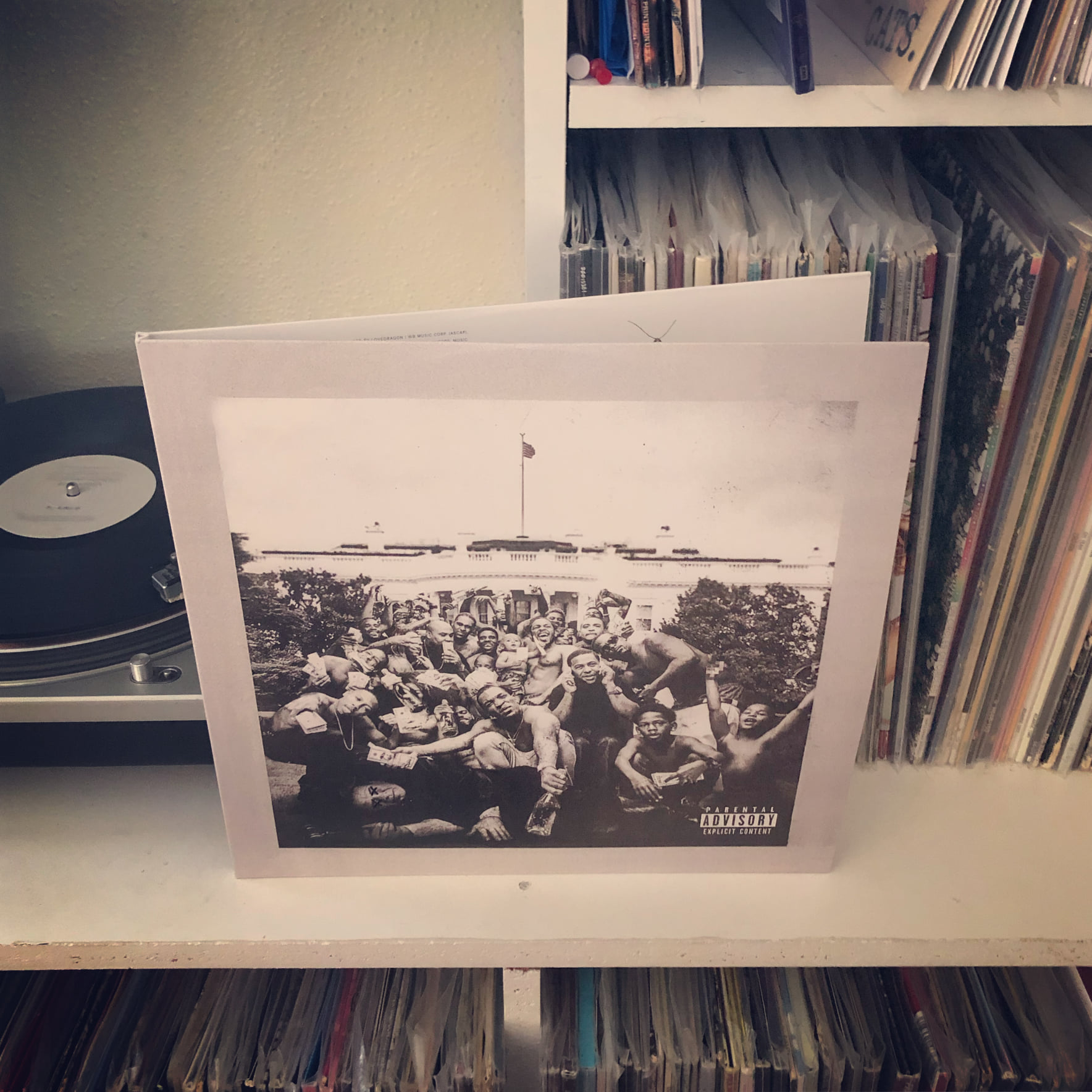

A lot of that disorientation came from this record, an eighty-minute monster filled with the densest verses around. But a few weeks ago, I decided to dive into it, and I can’t escape its grasp.

When this record came out, it was impossible to ignore. It was a fixture on every record blog’s photo roll. It topped nearly every year-end list. It stayed on Spotify’s front page for like, two years.

And so of course, unable to escape the hype, I gave it a listen. It was an objectively excellent record, but it didn’t feel like it was for me. It was too tied to the Black experience for a white kid from the suburbs to be able to relate (listening to it in the car gives me definite Michael-Bolton-in-Office-Space feels).

References to slavery, disenfranchisement, police brutality, and more social ills are hidden in metaphors several layers thick. Perhaps the most obtuse is the interlude “For Free?” wherein a woman threatens to cut off her deadbeat boyfriend, who then rebuts that “this dick ain’t free.” As it goes on, it becomes evident that the girlfriend is the United States and the boyfriend is the Black Man, having broken his back to build the country only to be met with broken promises (“I want forty acres and a mule, not a forty ounce and a pit bull”). “King Kunta” is a similar analogy, offering an attack on America’s fetishization of Black culture disguised as an “I’m famous now” middle-fingered diss track. The sexy, slinking “These Walls” feels like a pretty standard bedroom song, but then he turns to the not-so-sexy things the walls have seen—nervous breakdowns, rent hikes, abuse…

As if that weren’t dense enough, Kendrick has the tendency to adopt different voices. It almost feels a bit like a rap opera, each voice representing a different character that emerges, delivers a soliloquy, and makes his exeunt. Most notable is the Black Lives Matter anthem “Alright,” where he slips into the exaggerated Southern drawl of a man sixty years his elder. “For Free?” finds him emulating a smoother-than-smooth jive cat beat poet.

But when he drops the characters, the metaphors, and the drama, it goes off. The late track “The Blacker The Berry” is an aggressive—and sobering—look the problems facing the Black community in the 21st century, between police brutality and gang violence (“So why did I weep when Trayvon Martin was in the street? / When gang bangin’ make me kill a n***** blacker than me?”). “How Much a Dollar Cost” puts a lecture on cycles of poverty to the tune of a laid back R&B beat. The last seven minutes of “Mortal Man” is literally just a conversation between Kendrick and Tupac Shakur (created with audio of a rare interview) about hip hop and Black rage as a catalyst for social change. “i” is a jubilant piece of self-celebration (both in the personal self and the communal self), punctuated by the fact that Black lives are cut too short too often to let yourself waste a second not celebrating being alive.

Man, I haven’t even said anything about the production. The beats on this record are absolutely incredible. They draw richly from jazz, electric pianos and horns mingling under the bass-heavy percussion. There’s also plenty of nods to old school hip hop and 90s R&B, as well as some experimental-leaning tracks (opener “Wesley’s Theory” has moments that remind me of Coheed & Cambria, as if that makes any sense at all).

I still don’t feel like this record is for me. But, I realize now just how important it is for me to give it attention. While all the hip hop I usually listen to seems to want to be at least a little palatable to white kids in the suburbs, To Pimp a Butterfly doesn’t care that I’m listening. It is unapologetically Black, refusing to edit itself for listeners that might not Get It™. And as such, it is an incredibly important record, richly rewarding for those who let themselves get steamrolled underneath it.