Few musical movements are as weird, wonderful, and influential as Krautrock, a collection of West German bands in the 1970s that pushed the boundaries of what music could actually do to its extremes. The movement had an incredible influence on post punk, progressive rock, new age, shoegaze, and the birth of post rock. The shape of modern, electronic leaning pop music can be traced back to Krautrock, specifically the synthpop pioneers Kraftwerk.

Few musical movements are as weird, wonderful, and influential as Krautrock, a collection of West German bands in the 1970s that pushed the boundaries of what music could actually do to its extremes. The movement had an incredible influence on post punk, progressive rock, new age, shoegaze, and the birth of post rock. The shape of modern, electronic leaning pop music can be traced back to Krautrock, specifically the synthpop pioneers Kraftwerk.

But perhaps no band in Krautrock was more influential than Cologne’s Can, whose sprawling jazz-and-funk jams, improvised vocals, psychedelic exploration, tape editing techniques, and ambient experimentation went on to define Krautrock and influence everyone from David Bowie to Radiohead to Joy Division to the Flaming Lips to Kanye West.

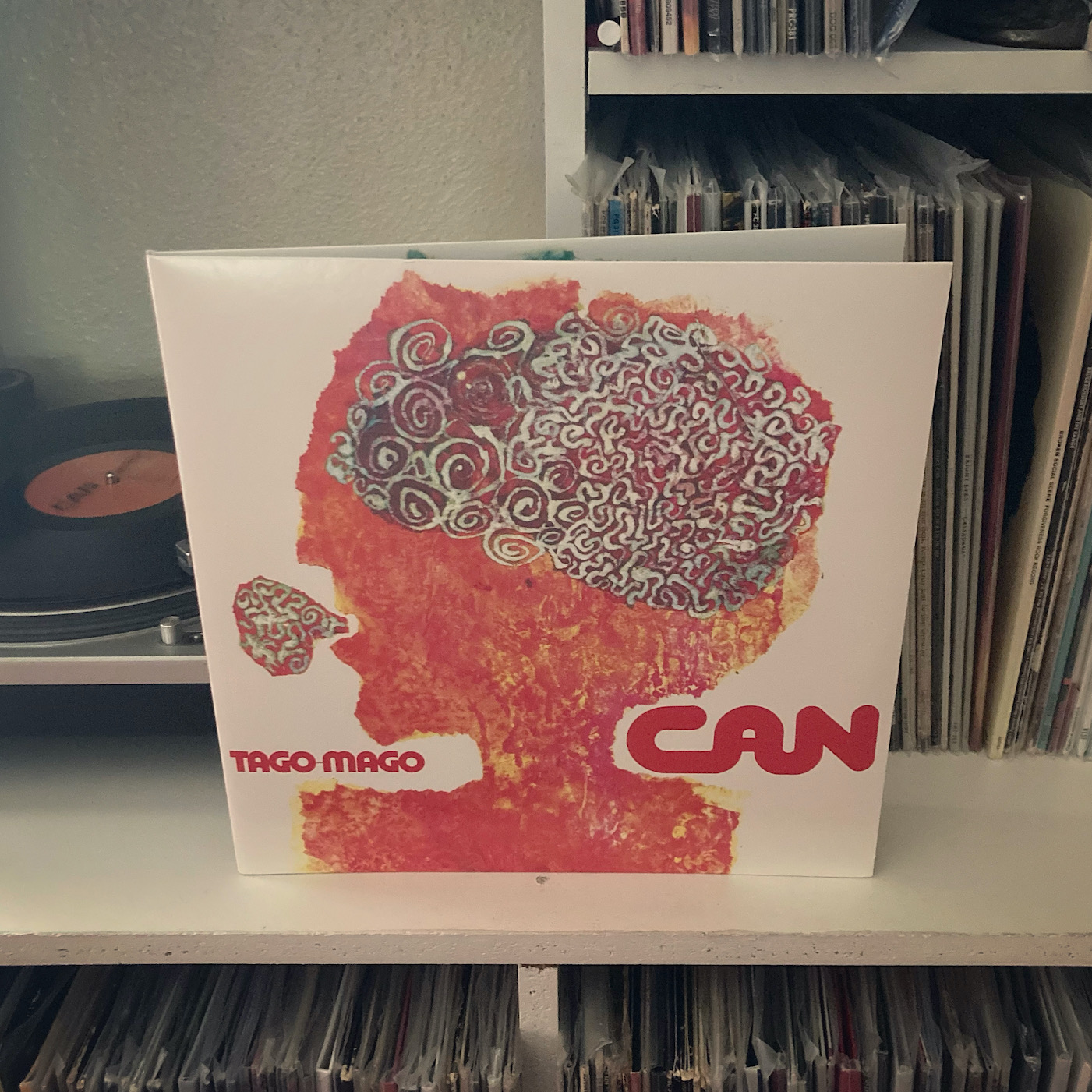

Among their monstrous catalog (they recorded ten albums between 1969 and 1979), most fans and critics agree that the pinnacle of their career was the trilogy of records featuring vocalist Damo Suzuki, which includes the criminally underrated Future Days, the seminal Ege Bamyasi, and this, the eldritch, immense Tago Mago.

Tago Mago is only the band’s second release, but it would go on to define the Can sound for most of their career. Following the departure of original vocalist Malcolm Mooney, bassist/producer Holger Czukay and drummer Jaki Liebezeit encountered Damo Suzuki, a Japanese musician, busking outside of a cafe in Munich. Czukay introduced himself and invited Damo to join his experimental rock band. Damo performed with Can that night and became a permanent member.

Later, the band was invited by an eccentric art collector to live in a castle he had purchased for a year, rent-free. Schloss Nörvenich, as the castle is called, became the home to the sessions that would become Tago Mago. For three months, Can would play for several hours a day, recording onto two-track tape with three microphones, utilizing the natural reverb of the castle’s high entrance chamber. At times, Czukay would also secretly record the band jamming while he “worked out problems with the equipment.” He then edited the tapes of these jam sessions into more organized songs, a technique utilized by Teo Macero for Miles Davis’ In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew (among others).

If that sounds like a chaotic way to create a record, that is reflected in the finished product, which is one of the most charming bits of controlled chaos put to tape. The record is a double album, the first disc focused on more conventional songs while the second disc features lengthy abstract noise passages.

The first disc isn’t necessarily too bizarre—by Can standards. The first side is bright and inviting—maybe even catchy. The songs groove on funk rhythms and traded improvisations between Suzuki, guitarist/violinist Michael Karoli, and keyboardist Irmin Schmidt. “Paperhouse” opens the record almost morosely, the band practicing restraint in a minor key. It doesn’t last long though, as two minutes into its seven-minute runtime, Liebezeit switches to double time and the band erupts into an energetic jam session. “Mushroom” is practically a pop song, clocking in at a hair over four minutes and having some semblance of a chorus. “Oh Yeah” pairs ambient keyboards and a strict, no-frills groove from the rhythm section accompanying Suzuki’s reversed vocals. The song quickens as it builds, guitars and keys rising higher in the scale while Liebezeit keeps groove steady—until the ending moments where he can’t handle it anymore.

Then there’s side B’s “Halleluwah.” It doesn’t feel like too much of a jump from the previous tracks, except for the fact that it’s eighteen and a half minutes long, making it as long as the first three tracks combined. Damo yelps and howls, his vocals babbling between English, Japanese, and gibberish. Karoli switches between guitar and violin a few times, his playing marked by bluesy bends and jazzy noodling. Schmidt likewise moves between organ, electric piano, and synthesizer, filling the space however he can. The rhythm section however plays with remarkable restraint, tethered firmly to the ground while the rest of the band soars at the end of the rope like a kite.

But no matter of improvised, atonal, freeform weirdness can prepare the listener for the second disc. The C side is comprised entirely of the track “Aumgn,” an ambient monster of tape loop experimentation. It opens with sparse notes from Karoli, his guitar run through a tape echo machine pushed to the extreme. Then, it shifts to a plinky keyboard phrase before being swallowed by echo-heavy bowed strings from Karoli’s violin and Leibezeit’s upright bass. Percussion joins in with some vocal weirdness from (checks liner notes) Schmidt, similarly warped by the echo machine. Later in the track, Schmidt trades his synthesizer for a sine-wave generator and oscillators, creating an eerie sci-fi whir. Toward the end of the track, Liebezeit finally adds a coherent rhythm, a quick double-time beat racing as oscillators rise ever higher until the noise collapses.

But “Aumgn” is almost easy listening compared to “Peking O,” which uses the same style of noisy experimentation but takes it to a terrifying extreme. There’s maybe more semblance of structure, but the individual movements are far stranger. Suzuki babbles and hollers, a drum machine sets a relaxing groove only to have its tempo turned to chaotic extremities, carnivalic organs burst and evaporate without notice with poorly played trumpets sputter against them, and horror movie strings stab and shriek. There are some moments that are almost catchy, but they are brief and bizarre. Paired with “Aumgn,” it’s an adventurous, if not necessarily listenable pairing. I for one am not totally averse to noisy experimentation like this (I did buy this record, after all), but at twelve minutes of all-out cacophony, “Peking O” probably isn’t going to end up on my Can mix.

The closer, “Bring Me Coffee or Tea,” returns to the more conventional (but still out-there—this is Can, after all) song structures of the first disc, and after the previous thirty minutes of music, it is a welcome relief. Even out of context though, it is a delightful song. The band is subdued playing a Raga-inspired riff, Suzuki singing sweet, but still strange, lyrics to a lover. In the refrain, he sings “I feel pretty in the chimney, I feel, / You just smile at me, / You’re just on my knee, / Bring me coffee or tea, / Call me ‘pretty little bee.'” It’s almost pastoral, and musically, it’s one of the closest things to a ballad in Can’s catalog. You might even call it beautiful. Karoli’s guitar is run through effects to sound like a sitar, Liebezeit’s drumming is restrained but still kinetic.

Today, it’s easy to look at Tago Mago in the context of its successors. It’s not quite as beloved as Ege Bamyasi, nor as accessible as Future Days (which is structured almost identically to the first disc of this record). Other acts would later utilize the tape editing techniques of the two noise tracks to more effective and musical ends. But, to do that is to forget just how innovative this record was. As long a shadow as Can has cast on nearly every corner of pop music, their influence begins here. Their debut Monster Movie might have showcased the band’s almost telepathic interplay, but Tago Mago is the album where they became the Can that has inspired legions of musicians in every genre. And the fact that something this bizarre and innovative was released fifty years ago makes it even more impressive.