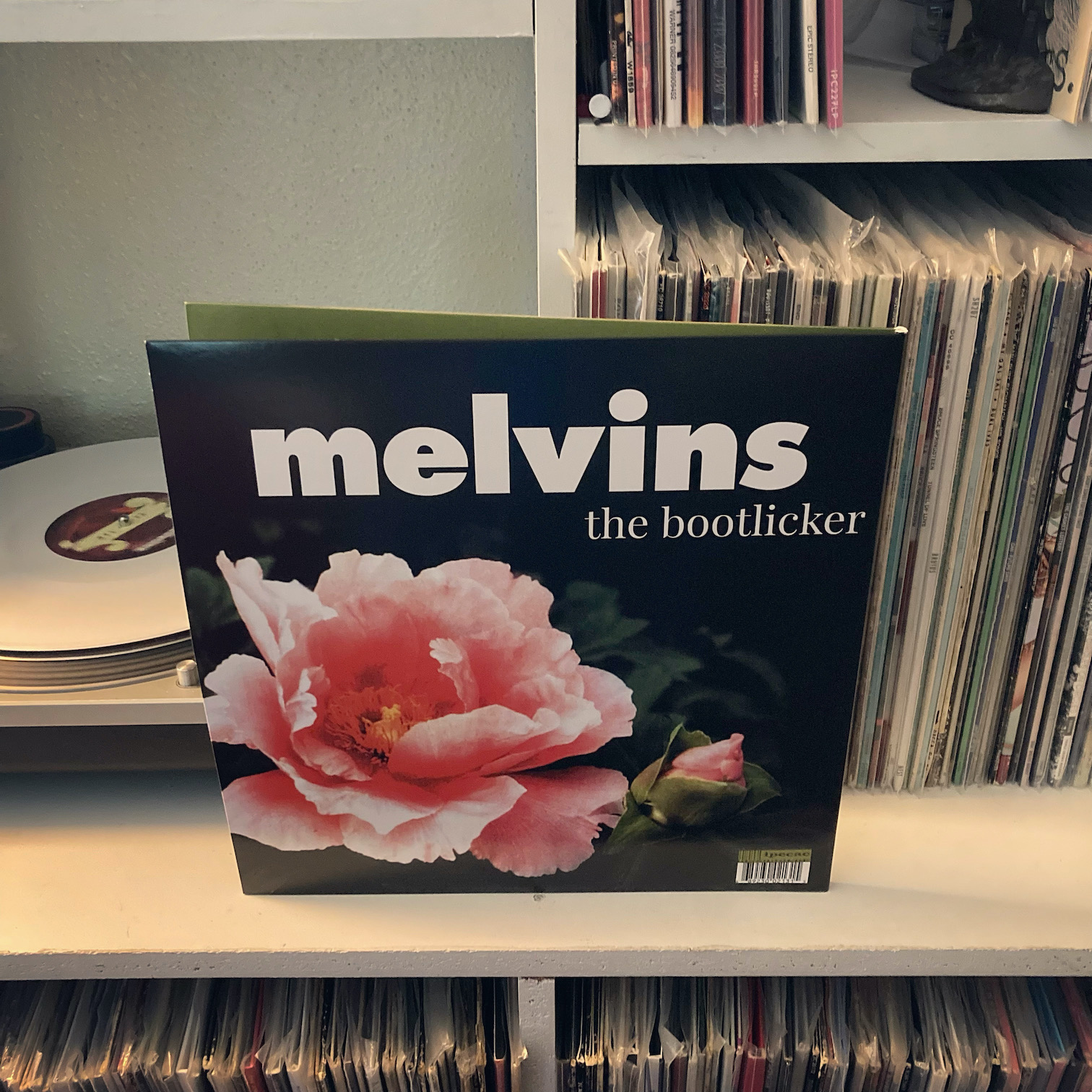

While it’s difficult to distill the whole of Melvins’ eclectic essence into a single release, the Trilogy, released between 1999 and 2000, came pretty close to doing so between three records.

While The Maggot saw them indulging their most volcanic heavy metal instincts, The Bootlicker was almost a complete rejection of their metal influences, exploring elements of jazz, funk, and psychedelic. In fact, many refer to The Bootlicker as one of the band’s most “pop-oriented” albums. But given that we’re talking about Melvins, there’s still plenty of wonderful weirdness here.

One of the most obvious idiosyncrasies of this album is the fact that it features almost no distorted guitars—which is a bold choice for a band who built their career on the aural magma that was their guitar tone. Additionally, Buzz Osbourne’s trademark growl is absent, his vocals instead delivered much more delicately, or on occasion, in a haunted house style cartoon baritone. However, there’s enough going on here that it’s hard to lament the change.

After the subdued funk-rock of opener “Toy,” the album delivers its first opus. “Let It All Be” is an eleven-minute journey through Can-esque meditative psych-rock, a drone interlude bridging two separate songs into one track. That track is followed by “Black Santa,” a plodding and plaintive song that makes tasteful use of pitch-shifted guitars and some compositional shifts reminiscent of Syd Barret-era Pink Floyd. “Up the Dumper” sounds like it might have been a classic rock hit if it was played with a bit more volume and sung with a more conventional singing voice.

Side 2 opens with “Mary Lady Bobby Kins,” which spends its first couple minutes in a languid tempo before pumping up into an almost uplifting, uptempo jam. That mood shifts back immediately with Kevin Rutmanis’ ominous bass riff of “Jew Boy Flower Head,” which feels like a standout simply for how stripped down it is—Buzz’s guitar is only present for a few brief moments across its six-minute run time. “Lone Rose Holding Now” is atmospheric and haunting, both Buzz’s voice and lead guitar coated with reverb and octave effects as Dale Crover’s drum beats experiment with some faux-Latin rhythms.

As experimental as everything on this disc is though, it all sounds practically tame compared to the nine-minute closer “Prig.” Electronic drum beats, cat impressions, and broken synths create a glitchtronica opening section, which fades after a couple minutes into a noisy drone section. After a few minutes that seem designed to get the listener to turn off the disc, an acoustic guitar strums, joined by drums, bass, and a piano. If it weren’t for the chaotic five minutes that preceded it, you might expect Bob Seger to start singing. Osbourne’s voice isn’t quite as impassioned, but this might be the best he’s ever sounded. Once it fades out, the first few bars of their cover of “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” the opening track on The Crybaby plays, which makes it all the more curious why the third album in the Trilogy wasn’t included on the recent run of reissues.

Given both its initial release in The Trilogy and the reissue that bundled it with The Maggot, it’s difficult to know if The Bootlicker would stand on its own as a standalone record. It’s maybe too married to the context of its companion albums—and the extended Melvins discography—to be heard without comparing it to their other work. Regardless, it is a truly weird and wonderful album, even among their entire weird and wonderful body of work. Even in a discography as stuffed with experimentation as theirs, The Bootlicker manages to be a standout. It might not be their best record, but it’s certainly one that makes you pay attention.