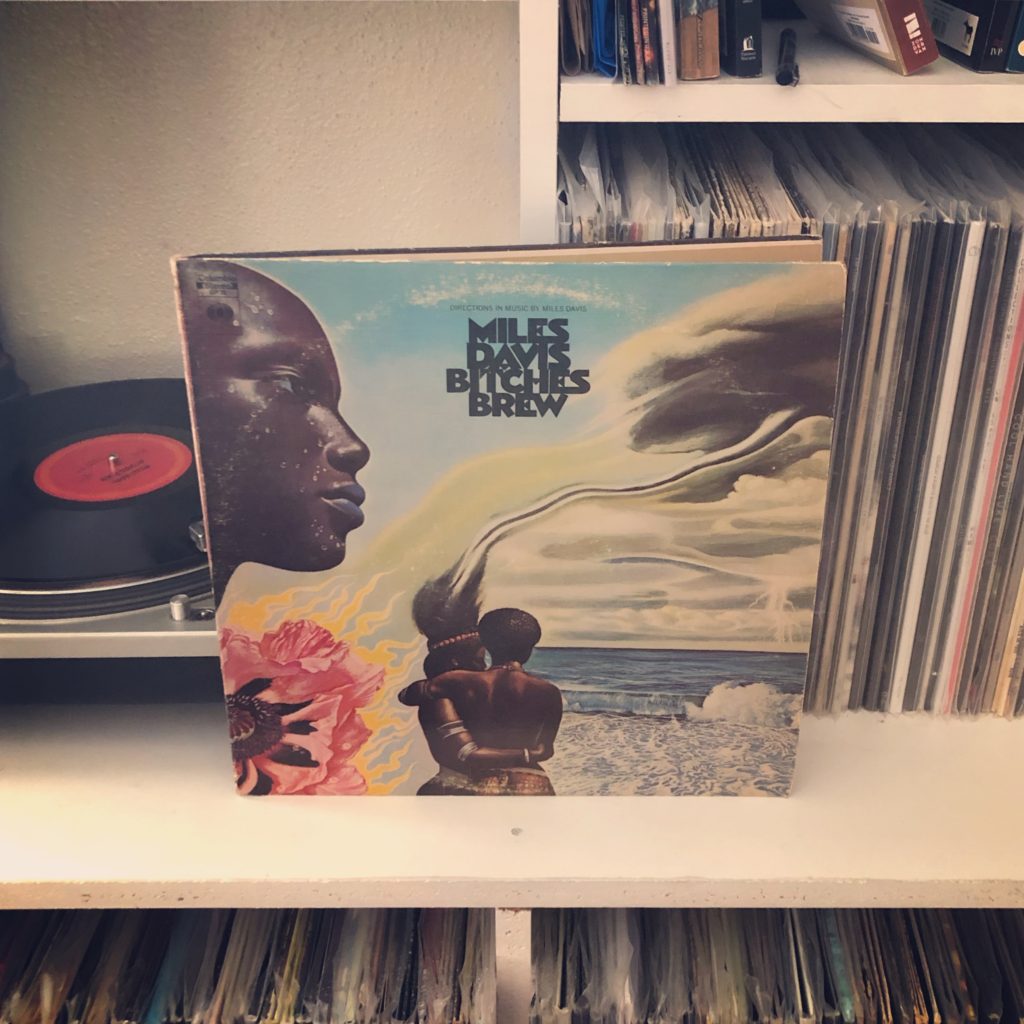

If you mention Miles Davis among older individuals, you might get an almost dismissive, “Oh, he’s too weird for me.” Almost invariably, they’re talking about Bitches Brew, his 1970 jazz fusion opus.

And brother, it’s as weird as advertised.

After the electric grooving of In A Silent Way, many in the jazz community rejected Davis’ new direction. They thought he was selling out by adopting the instruments of the devil (read: rock and roll). They called producer Teo Macero a heretic for editing the tapes of the performances.

But Miles was undeterred. Instead, he doubled down—quite literally, if we’re talking about his rhythm section. The band here includes two full drum sets, an upright and electric bass, two electric pianos (just Joe and Chick—Herbie sat this session out), and two percussionists. He’s also joined by his stalwart saxophonist Wayne Shorter, bass clarinetist Bernie Maupin, and once again John McLaughlin. Interestingly enough, after just one previous collaboration, John has a song named after him here (strangely enough, Miles does not play on that track).

Macero’s work is particularly revolutionary here. While In a Silent Way was spliced out of a few large sections from a three-hour recording session, Bitches Brew’s three-day session was chopped up and pieced together with an almost complete disregard for the original source material. In “Pharaoh’s Dance,” a one-second loop is spliced in several times across the running time. He added echo and other special effects in post—a practice that was unheard of at the time. In that way alone, this record would be the predecessor of dub reggae, Can‘s Tago Mago, the Mars Volta, and much of EDM.

Unlike Davis’ previous other records, very little was rehearsed for this record. The musicians were called on short notice with no music to go off of. Davis’ directions were as vague as possible. Often, he would just give them a key, a tempo, and a mood. The rest was directed on the fly—Davis’ voice is even audible through some of the quieter moments. But through the lack of direction, there is an incredible freedom to be found. The group plays here with a wild, untethered abandon. This isn’t anything like free jazz, mind you—free jazz operated much like a free-for-all. Players would chase after the limits of their instruments near eachother, but not necessarily in cooperation with eachother. But here, the musicians are entirely aware of what’s going on around them. They might be playing different rhythms or different motifs, but they are locked in to the same groove. As rabidly as they play, they are still united in purpose to the band. Miles himself is not immune from this manic, heathen energy. While he had typically been noted for his restrained, economically solos, here he is explosive.

Bitches Brew is often noted as the album that kickstarted the jazz fusion movement. But this record is far wilder than the funk-flavored fusion that groups like Zawinul’s Weather Report would innovate, and it is worlds ahead of any rock groups trying to adopt jazz influence (looking at you, Steely Dan). Bitches Brew is something else entirely. It is a wholly singular record, not only in the context of Davis’ career or the history of jazz, but in the whole of recorded music. In A Silent Way may have been a turning point for Davis (and I do prefer that record), but it was still retained much of Miles’ trademark cool jazz stylings. Bitches Brew is the sound of Pandora’s Box opening, and Davis had no intention of putting any of those monsters back inside.